The first time my dad met Joseph Lucky Gribble, he was fighting some

garbage men near the Burger King by my Gramaw’s house in Fairfax. It was

the 1960s. Dad and Lucky were fast friends.

My most vivid memory of Lucky is him standing perfectly still for

hours, cigarette smoldering between his fingers, his eyes staring out

the plate glass window of my dad’s VW repair shop in Fairfax.

I’ve never seen anyone stand so completely still for so long.

For a while Lucky slept in a loft at my dad’s shop, and for years had

a plywood shack on the grassy corner by Montgomery Ward in Fairfax,

near where Burlington Coat Factory is now. Sometimes he would disappear

for days, then return, like nothing had happened. He rode a yellow

Harley and drank endless cups of black coffee while smoking cigarette

after cigarette.

Sometimes I would work for Dad at his shop in the summers. When I’d

get to work, I’d ask where Lucky was, and Dad’s answers would range from

“He’s in a mood today,” to “Sleeping in a car,” to “In the bay, working

on a car,” to “I don’t know. He disappeared again.”

I always accepted Lucky for what he was. In a bad mood? Don’t talk

to him. In a good mood? Brief but interesting conversations, an

extremely intelligent man with deep brown eyes that would dart this way

and that, like he was expecting something to sneak up on him and hit him

with a length of pipe. His eyes would meet mine for a tiny moment then

flit away.

One day at the shop, Dad put Lucky and me to work stripping a VW for

parts. Lucky asked me about my life, expressing a genuine interest. We

had slow conversation most of the day while removing everything we

could from the Beetle, his cigarette smoke burning my eyes when it

wafted my way. I was fifteen.

Every once in a while, Lucky would bring me little gifts or send

things home for me with Dad. Usually it was Harley stuff, and I

appreciated the thought behind it. In return I made for him his

favorite: Gingerbread. These past few years, when Dad and I would

visit him, Lucky would give me Bluegrass CDs, their cases thick with

dirt.

One day it occurred to me that while this was normal behavior for Lucky, this was not normal behavior. So I asked.

“Dad, what’s wrong with Lucky?”

“That’s what too many drugs will do to you, Angie.”

My mom always said of Lucky, “He used to be so good-looking, all the girls just loved him. Really intelligent, too.”

At another time, wondering what would leave a person standing and

staring for hours, cigarette smoldering down to the butt, I asked my

Dad, “What kind of drugs did Lucky do, Dad?”

“PCP.”

Shit.

After being evicted from his squatter’s shack when they built the

shopping center where Burlington Coat Factory is, Lucky disappeared for a

while. I would ask Dad about him, how he was doing, and sometimes

there would be a sighting (7-11 off Jermantown Road, mostly).

Occasionally he would help Dad with things like putting new roofing on a

building (While they were working, Dad rolled off the roof and landed

in the bushes. Lucky laughed until they realized Dad’s wrist was

broken). Eventually he moved into a house in the woods off Braddock

Road and Dad would visit him there. It was a ramshackle little house

and he parked his yellow Harley in his living room, choosing more often

to drive the old blue and white Chevy truck my dad sold him for a little

bit of nothing.

One day Lucky appeared at my parents’ house, while I was visiting

them, to help Dad with something. I hadn’t seen him in years. He

looked older but the same, except for a few missing teeth. He was lanky

and tall, deeply tanned, black hair combed back, and his brown,

bloodshot eyes nervously darted around, still anticipating that length

of pipe. I hugged him and he smelled as he always did: Unwashed and

smoky. By this time I had Peony; she was still a baby. I proudly

showed her to him. He wouldn’t look at her because he said he was

afraid if he did, he would “make her retarded.” I told him it would be

okay, but he was too uncomfortable and I let it go.

Over the years, my Dad would go by Lucky’s home, where ever he was

living at the time, and bring him clothes and food and visit with him.

Lucky’s shack on the corner of Jermantown Road, my dad told me, was

insulated with clothes hanging on all the walls. A small woodstove

helped keep him warm. A couple times after he moved into the house in

the woods off Braddock, I went with Dad to visit him, but you never knew

when Lucky would be there. He was sort of a nomad, most certainly a

loner.

I once told Dad how my friends said if there was an apocalypse, they

were all going to find him because he’s so handy with, well, just about

everything. Dad said, “Shoot, I’ll be with Lucky. He can live anywhere

and survive anything.”

Lucky was a strange bird for sure, but there was something gentle and

almost otherworldly about him. He had a temper I’d only heard about,

never saw. And while he had no connection to anyone or anything, he had

great respect for my Dad, and despite some of the choices Lucky made in

his life, my Dad respected him and cared about him. When no one else

was there, my Dad was, and he didn’t pass judgment.

Every time after we’d go visit Lucky, I’d think, I really wish we

would do that more often. The last time I saw him was when I was

pregnant with Cedar, winter of 2010. Dad, Peony, and I stopped by with

gift bags full of homemade gingerbread and coffee. Lucky had moved his

living space to the basement of the old house in the woods. He had a

wood stove in the corner and it was warm, cozy, and smoky. He gave us

bottled root beer to drink and when we left, he sent Bluegrass CDs with

us.

As we were leaving, I hugged Lucky goodbye and wished him a Merry

Christmas. I sent a few things to him once after that, when I knew Dad

was going to go by his place: an

O Brother, Where Art Thou soundtrack, food, cash. The other times we stopped by together, he wasn’t there. Always a mystery, that Lucky.

Always a mystery.

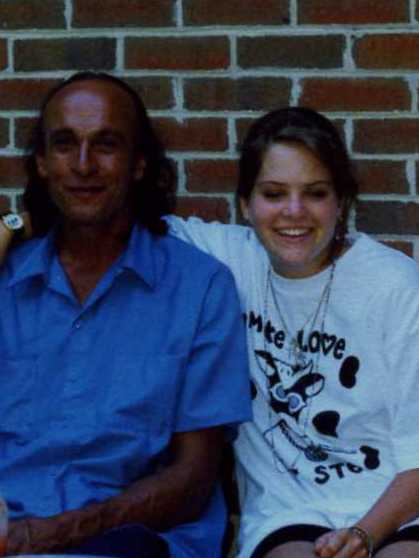

- Lucky and Ang at High School Graduation Party, June 1991

"Joseph Lucky Gribble, 64, of Fairfax, died on Saturday, March 24, 2012, in Fairfax.

He was born on November 9, 1947, a son of the late Franklin Silvester Gribble and Elsie Gray King Gribble. He was also preceded in death by a brother, Robert Harvey Gribble. Mr. Gribble is survived by a sister, Margaret Octavia Horseman of Ellicott City, Maryland; and a brother, Tennis Silvester Gribble. Funeral services will be held 2 p.m. Thursday, March 29, 2012, at Preddy Funeral Home Chapel in Madison."